Barriga llena, corazón contento

Con mis dos hijos, con casi una década de distancia en el medio, he asumido dos maneras distintas de presentarles el viaje infinito que es la comida.

Con mis dos hijos, con casi una década de distancia en el medio, he asumido dos maneras distintas de presentarles el viaje infinito que es la comida.

Dar la teta cansa, restringe tu movimiento, te encadena a tu hijo; y a la vez es lindo, placentero y cómodo en muchos aspectos.

Con el tiempo me fui dando cuenta de la importancia de los límites del «no». Romper también es una forma de aprender a crecer.

En el debate sobre la interrupción voluntaria del embarazo las mujeres son revictimizadas: su libertad, su voz, su voluntad, no suelen estar en el centro de la discusión, aun cuando es su cuerpo el territorio en disputa.

Muchas teorías parecen culpar a las mujeres por su «egoísmo». Me resistía a la idea de ser una «mala madre» antes de que me dieran la oportunidad de demostrar lo contrario.

Están en una situación muy difícil. Nadie sabe cuántos son ni cuál será su futuro al caducar su visado de turistas.

La etapa menos conocida de este ícono mundial de la música cubana, transcurrió en Cuba. La musicógrafa Rosa Marquetti Torres nos descubre detalles de Celia Cruz antes de salir de la isla.

Adriana e Irena fundaron Vitria, única cooperativa de vitrales en Cuba y una de las pocas conformada solo por mujeres. Dos jóvenes en un andamio de seis niveles o colgadas de un techo para restaurar vitrales dejaba a más de uno con la boca abierta.

Yailén Ruz, psicóloga y fotógrafa, se adentra en el mundo infantil de familias homoparentales cubanas y lo recrea a través de la imagen.

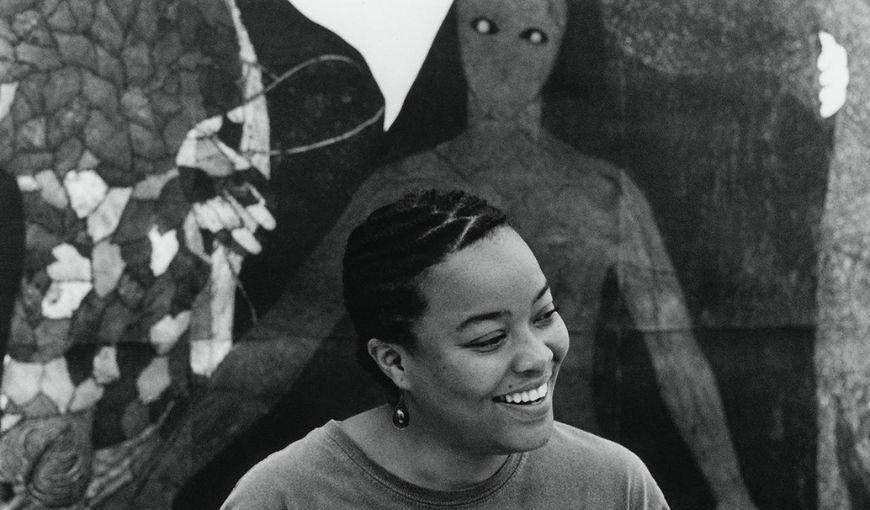

El 17 de noviembre el Museo Reina Sofía de Madrid inauguró «Colografías, Belkis Ayón», la primera muestra retrospectiva dedicada a la grabadora cubana en Europa.

Partiendo de los cuadernos premiados TroyanasenYouTube y Teatropeutas en YouTube (Canales para Heroínas), esta autora ha comenzado a llevar a diversas redes sociales el eco de sus textos

Su cuerpo delgado y su rostro casi infantil podrían hacerla pasar por una adolescente que experimenta entre sonidos y actuaciones, fotos y videos, publicaciones de redes sociales. Pero Malaka es toda una mujer y sabe lo que quiere… y lo que hace.

Testimonio de la psicóloga y profesora universitaria Carolina de la Torre sobre su hermano Benjamín, quien se suicidó en 1968 tras ser víctima de homofobia, en especial durante su reclusión en las UMAP en Camagüey.

La protagonista de la novela es una reportera venezolana radicada en México que atraviesa la crisis sanitaria y otras crisis relativas a su profesión, la persecución política y la condición de inmigrante.

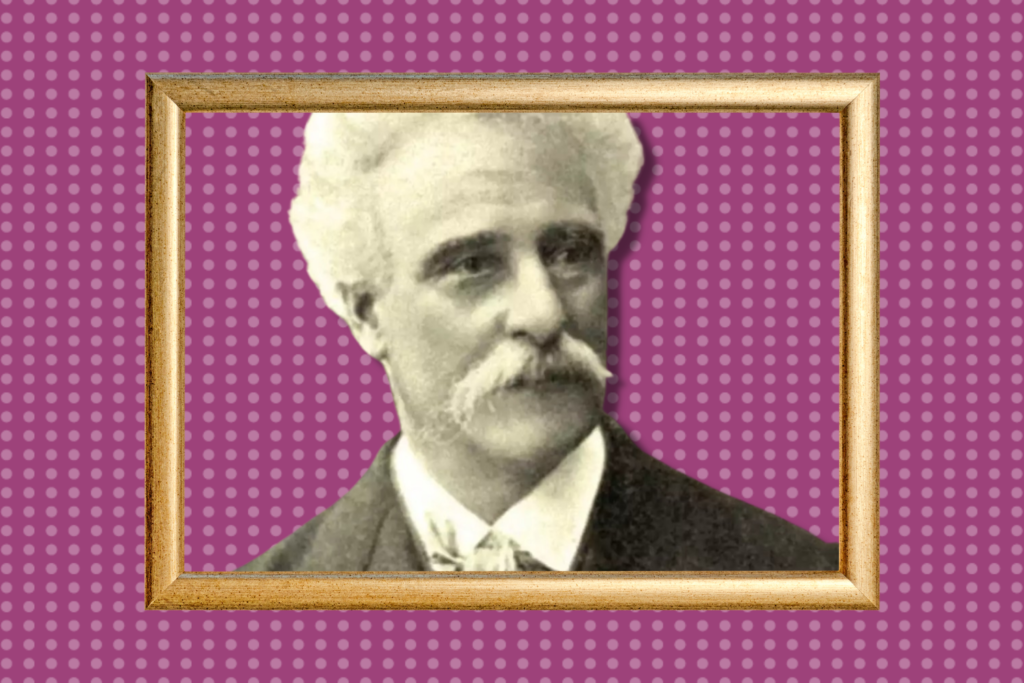

El ensayista, nacido en Santiago de Cuba en 1842 y fallecido en Draveil, Francia en 1911, firmó dos ensayos feministas, en clave marxista, rescatados recientemente: El matriarcado (1886) y La cuestión de la mujer (1905).

Nos gustaría que te suscribas al boletín de Matria. Lo recibirás solo una o dos veces al mes, directo en tu e-mail, con nuestras novedades y recomendaciones.